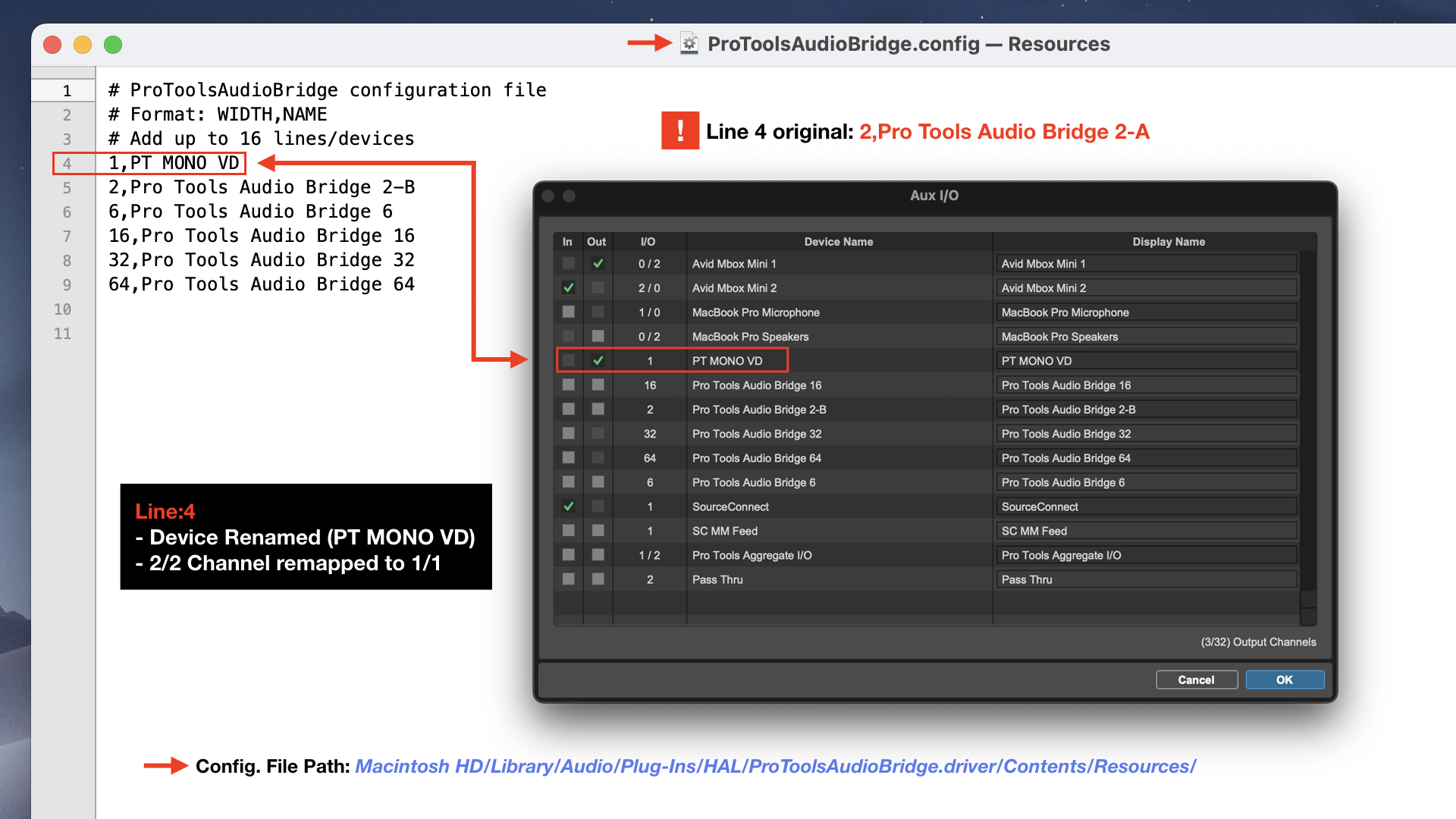

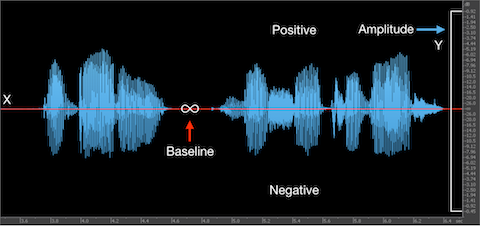

When considering best practice audio compliance guidelines for internet distribution [mobile, podcast, streaming, etc.] … processed intermediates may require significant up side gain adjustments in preparation for distribution encoding.

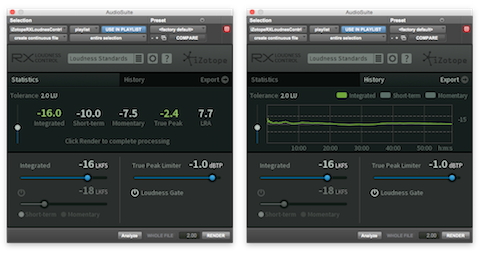

If you elect to apply offline Loudness Normalization, the process is simply (after measurement) a linear gain offset + limiting if necessary.

There are several [what I refer to as] pre-gain offset issues that all producers and engineers must be aware of …

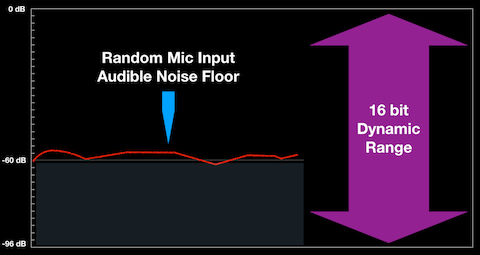

Noise Floor

This is rudimentary: adding gain will boost the audibility of preexisting broadband noise and possibly degrade audio fidelity.

A specific example where applied gain over noise is problematic ➝ post downward expansion.

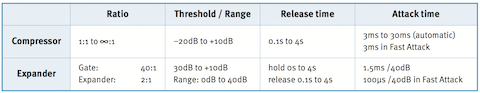

Are you under the assumption that applying downward expansion is a form of broadband noise reduction? It isn’t. The process does not remove persistent audible noise. When talent is actively speaking and the audio level is above a predefined threshold – residual noise will be audible as well.

If you think talent transitions from silent inactive speech passages to active passages with audible noise sound bad – imagine how this will translate after adding significant gain. Terrible.

In essence you must do whatever you can to mask [or attenuate] your noise floor prior to downstream processing. Just be careful. Heavy noise reduction will certainly introduce artifacts. Of course best case is to circumvent noise at it’s origin.

Breath Levels

Adding significant gain elevates breath amplitude. Pre and/or post gain optimization is paramount.

IMO in order to preserve natural human speech characteristics breath retention is vital. ‘Ever experience speech passages with all breaths cut and subsequent ripple edits applied? It sounds robotic and horrible. Yet there are cowboys out there that preach the technique suggesting “listeners do not want to hear breaths.” Questionable perspective in my book.

I do agree that breaths elevated in level or those exhibiting snap syndrome* may be bothersome to listeners.

There are several tools available that attempt to sense and attenuate breaths. As far as I am concerned the only way to properly optimize persistent breaths is manually, instance by instance. Sure it’s time consuming. So saddle up.

Limiting Considerations

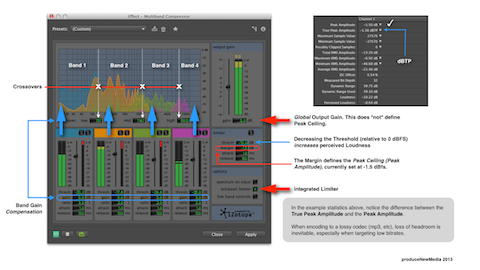

In order to adhere to a subjective spec. or a best practice imposed [true peak] ceiling – producers must assess how added gain will impact potential limiting requirements.

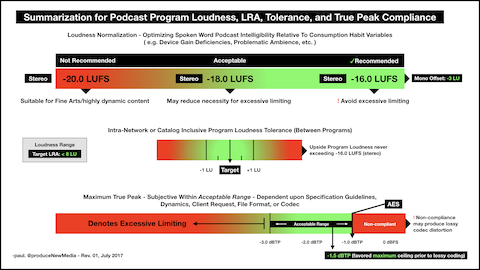

Do not ignore this fact: integrated loudness ‘targets’ for internet, mobile, and podcast distribution differ from broadcast specification description. You must produce audio intermediates (or mixes) that are prepped, optimized, and capable to sustain additional gain without compromising fidelity and/or nulling adherence to best practice or subjective specs.

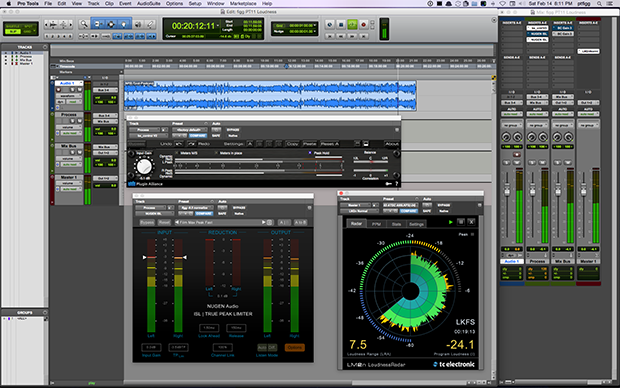

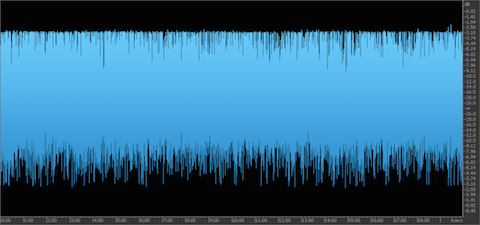

Whether you are driving your mix into a limiter ceiling (I don’t necessarily recommend this) or you are applying offline loudness normalization – limiting (in most cases) will be necessary.

The key of course is proper intermediate optimization before the audio is bumped up (or limited) at the final stage. In fact the goal is to avoid excessive limiting! Encoding heavily limited audio into a lossy codec is a work place hazard. Not a good idea.

What to do?

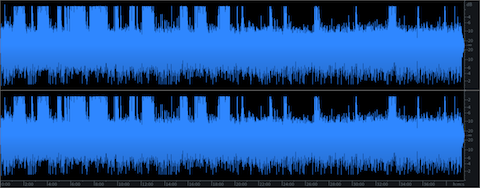

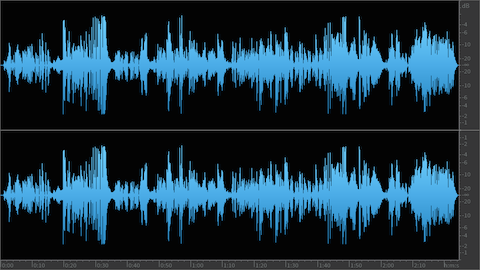

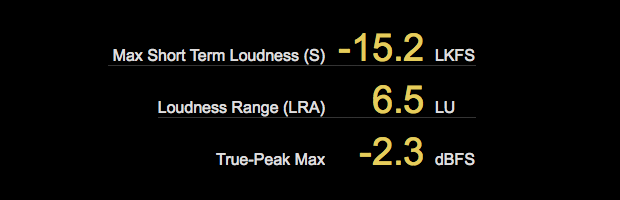

Assess the attributes of your audio prior to final stage processing. Be aware of available headroom. Gauge the amount of limiting that will be necessary to meet your compliance goals. If required limiting is excessive and there is even the slightest indication of audible distortion – revert and make changes.

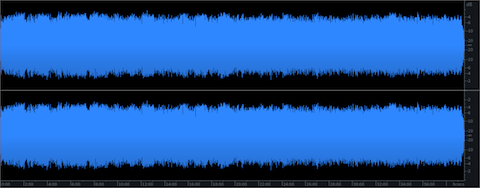

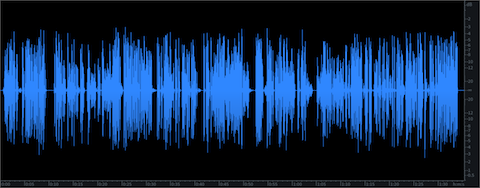

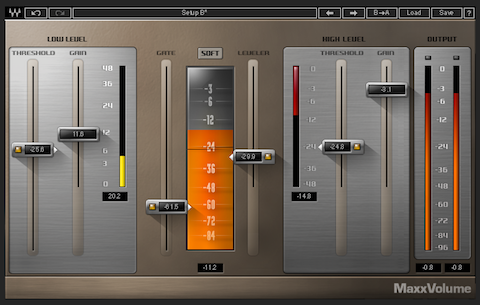

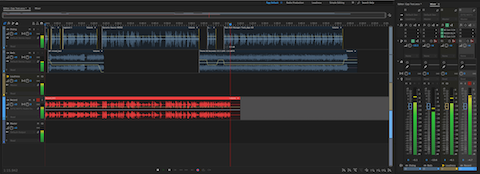

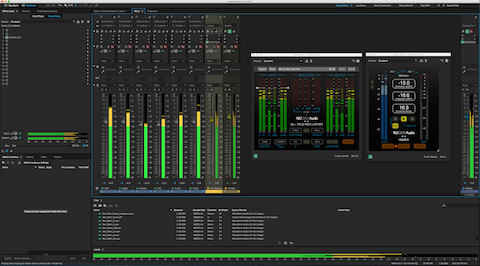

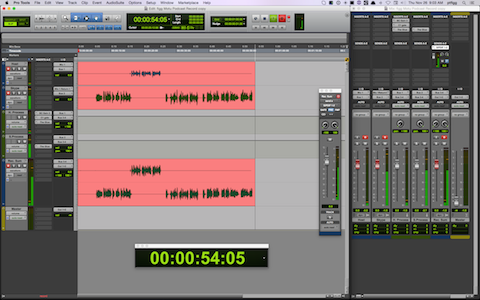

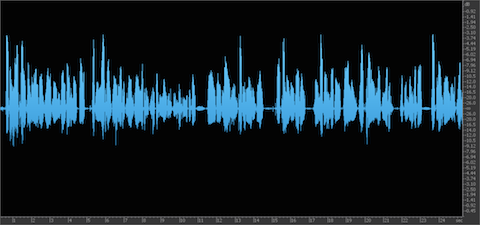

A technique that I frequently discuss and implement for speech/podcasts is what’s referred to as “glueing.” It is achieved by using a bus modeled compressor to tame dynamic transients and/or instances of inconsistent amplitude. If a final required gain offset is significant – a moderate amount of applied bus compression before loudness normalization will help alleviate the necessity for excessive limiting.

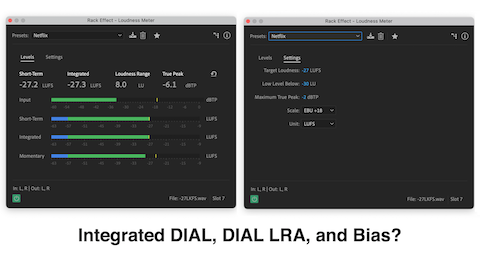

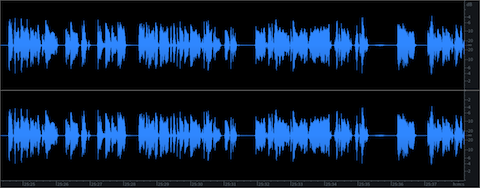

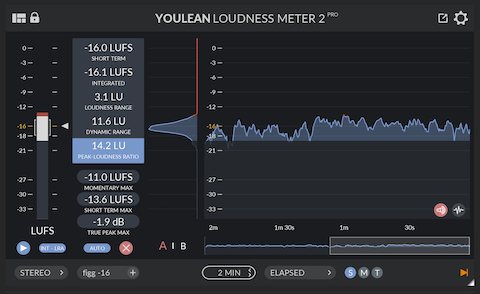

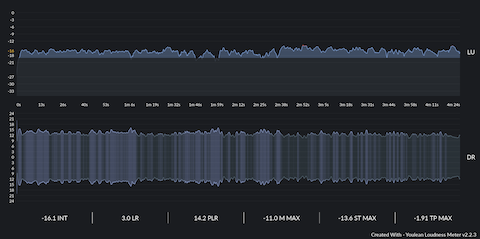

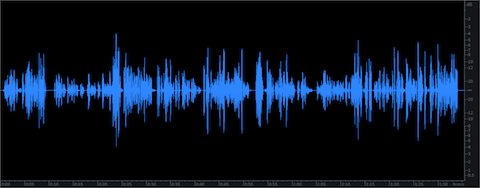

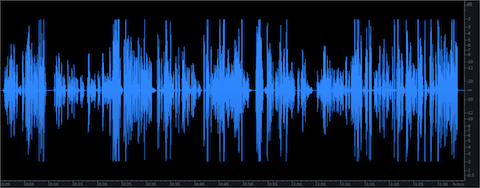

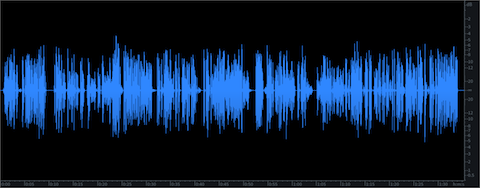

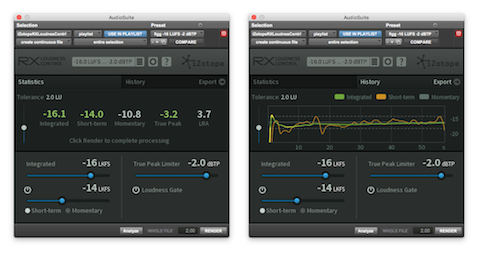

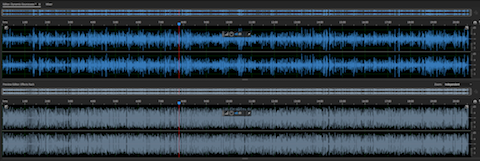

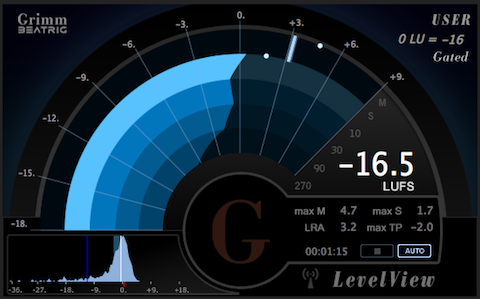

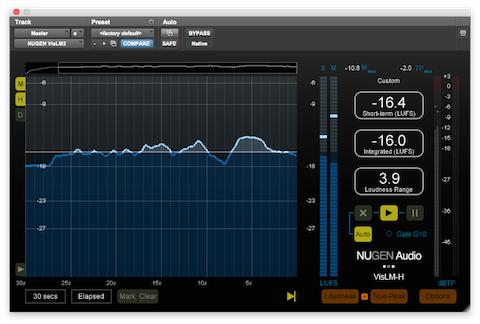

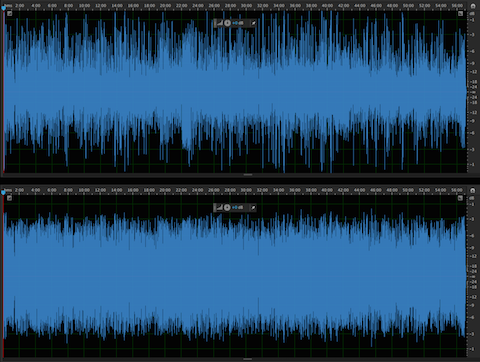

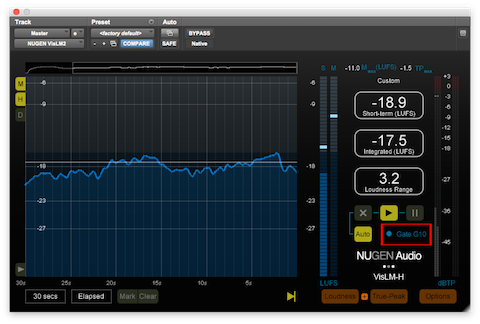

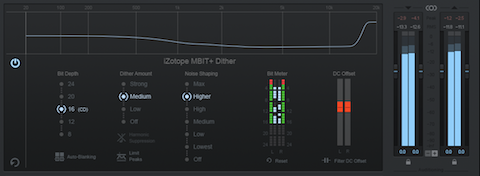

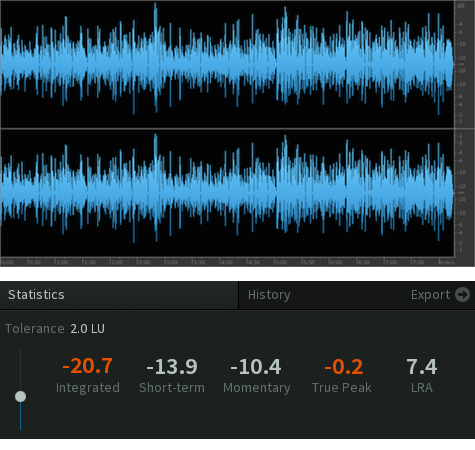

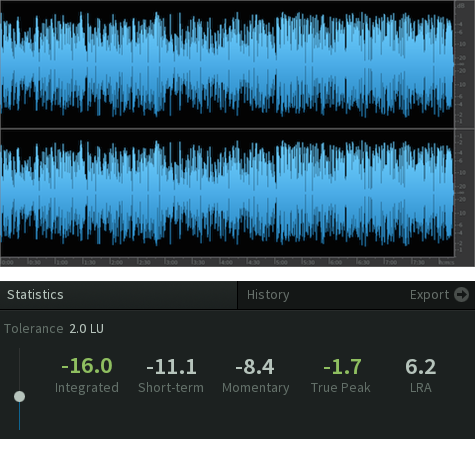

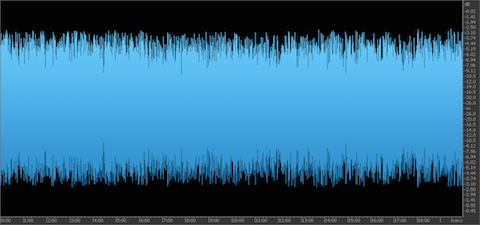

Example: processed/edited stereo intermediate checks in at -20.98 LUFS. Speech dynamics are far from optimized. Intent is a -16 LUFS deliverable, -2.0 dBTP ceiling.

I’m using the new version of Elixir by FLUX:: Immersive. You can insert it in a DAW session or apply offline.

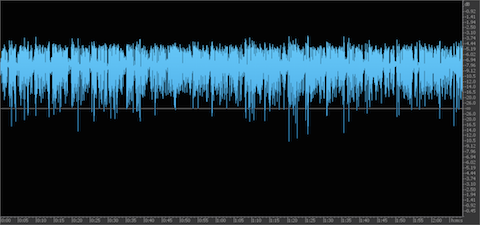

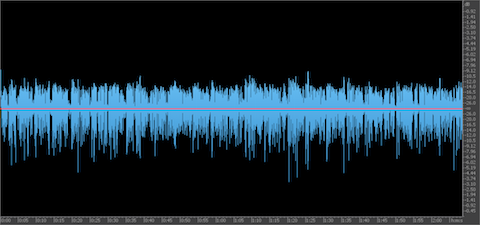

First I take the intermediate down to -24 LUFS: so input gain is set to -3.02 dB. Next the limiter threshold is set to -10 dB and the output gain is set to +8 dB. The integrated target and ceiling now comply. However notice the intermittent limiter gain reduction.

In this scenario I would contemplate re-mastering the intermediate and attempt to tighten things up. Maybe check for asymmetry. Apply bus compression and zone in on RT Short Term loudness description [3 sec. averaging window]. Tweak as necessary.

Anyway … when teaching or discussing how to create and supply high quality deliverables, we must not forget the foundational aspects of speech based audio production. Basic gain manipulation and associated ramifications are vital aspects of professional podcast production. So dig in.

-paul.

* What is “snap syndrome?” I’m fairly certain I coined the phrase. The anomaly occurs when talent breaths (when they inhale) exhibit a sudden snapping sound for whatever reason. I zone in and remove all audible instances.